Plight of Dhaka’s canals: How agencies failed to protect our waterways

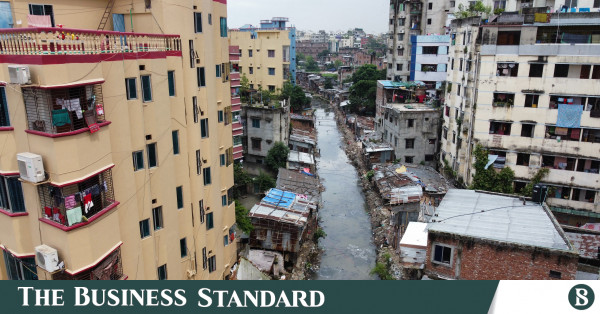

Dhaka, once crisscrossed by a network of natural canals that served as drainage and transportation routes, now faces a dire crisis regarding its waterways, due to rapid urbanisation over the past century.

Urbanisation has claimed at least 15 of Dhaka’s canals, replacing them with box culverts and roads. While government directives facilitated these projects, the consequences have been severe.

This loss of natural canals has impacted Dhaka’s drainage system, exacerbating waterlogging during the monsoon.

Despite numerous plans and initiatives, neither Dhaka North nor Dhaka South city corporations have succeeded in restoring the canals’ regular water flow after nearly four years of management.

Hundreds of crores of taka have been allocated for dredging and waste removal from the city’s 26 remaining canals, but progress remains slow.

City authorities cite encroachment and insufficient resources as major obstacles. Experts, environmentalists, and residents alike lament the slow pace of change and the lack of political will to address the issue.

Court orders and lack of implementation

In 2017, the High Court ordered authorities to prepare an action plan for recovering 50 canals in Dhaka, including reports on the current state of these canals and a list of illegal occupants and pollutants.

The Bangladesh Environmental Lawyers Association (BELA), which filed the original writ petition, argued that government agencies had failed to protect Dhaka’s canals from encroachment and pollution.

On July 27 this year, BELA Chief Executive Syeda Rizwana Hasan, now adviser to the environment ministry, told The Business Standard, “The reason for not complying with the High Court orders is the lack of coordination between the agencies and a mindset within the government that there is a low probability of being held guilty of contempt of court if the orders are not followed.”

Urban experts and environmentalists echo these concerns, noting that while policies and action plans for restoring Dhaka’s canals exist, proper implementation remains lacking. This failure is evident in the slow pace of canal restoration efforts over the years, despite numerous attempts by various city authorities and government agencies.

Dhaka Wasa’s struggles with canal management

For many years, the responsibility for maintaining Dhaka’s canals lay with the Dhaka Water Supply and Sewerage Authority (Wasa). However, Wasa’s efforts were riddled with delays, cost overruns, and inefficiencies.

One of the most notable examples was the Land Acquisition and Re-excavation Project, launched in April 2018 with a budget of Tk645.51 crore.

This project aimed to divert rainwater and household water to rivers via canals to alleviate waterlogging, yet by June 2021, only 7% of the project had been completed despite the expenditure of Tk39.09 crore.

Most of the funds allocated for the project were used for land surveying and acquisition, with little progress made on canal bank development or walkway construction.

Wasa officials attributed the delays to bureaucratic obstacles, lack of manpower, and insufficient funds.

A second project, the Expansion of Dhaka Metropolitan Drainage Network and Canal Development, was launched in 2018 with a budget of Tk550.50 crore, aiming to recover 16 canals and improve drainage.

By June 2021, 30% of the project was completed at a cost of Tk136.45 crore, yet many of the improvements were temporary. Canals quickly reverted to their polluted state due to the absence of long-term maintenance and poor enforcement of encroachment laws.

The canal banks were cleared, and embankments were constructed, but the cleaned canals rapidly filled with garbage again, and illegal structures were rebuilt.

A Tk20 crore project dedicated to embankment construction yielded minimal results, with limited work being executed on the Ramchandrapur Canal.

Dhaka Wasa’s Deputy Managing Director (O&M) Engr AKM Shahid Uddin cited a lack of manpower and resources as the primary obstacles.

He said, “We showed the project progress to the extent of the work done and returned the remaining funds to the ministry. Dhaka Wasa did not have the manpower or funds to maintain the 26 canals and drains assigned to them.”

BWDB’s similar challenges

The Bangladesh Water Development Board (BWDB) faced similar challenges.

In recent years, BWDB implemented the “Dhaka-Narayanganj-Demra (DND) Area Drainage System Development Project,” with a budget of Tk1,300 crore.

Officially completed in June 2023, the project involved the excavation of 14 canals. However, despite BWDB’s claims of success, the canals quickly reverted to their prior conditions due to poor maintenance and lack of oversight, nullifying much of the project’s benefits.

Dewan Ainul Haque, superintending engineer of Dhaka Water Development Circle-I in BWDB, noted that while the physical work on the project had been completed, the paperwork had not yet been handed over by the contractors.

“A significant portion of the project’s budget was spent on excavating the canals,” he said.

But as with Wasa’s efforts, BWDB’s canal excavation work was rendered ineffective by poor maintenance.

City corporations step in: Mixed results

In December 2020, the city corporations of Dhaka formally took over responsibility for canal maintenance from Wasa.

Of the 46 canals counted by the two city corporations, 29 are in Dhaka North, and 17 flow through Dhaka South. The two corporations have since focused on cleaning and clearing these canals, but progress has been slow.

Since 2021, Dhaka North has removed 3.27 lakh tonnes of waste from its canals and installed CCTV cameras at 24 locations to monitor illegal dumping.

The city corporation has also embarked on a Tk27 crore project to demarcate canal boundaries and construct pillars. As of mid-2024, pillars had been erected at 858 locations.

Dhaka North’s former mayor, Md Atiqul Islam, told The Business Standard in July, “We received jurisdiction, but we have not received any manpower or funds for maintenance. We are doing as much as we can with our own funds.”

He highlighted that the city’s canals had been neglected for 50 years, and reclamation efforts faced strong opposition from powerful encroachers.

In Dhaka South, the city corporation has launched a Tk900 crore project aimed at restoring four key canals: Jirani, Shyampur, Manda, and Kalunagar.

DSCC announced in August 2023 that it would begin an eviction drive to remove illegal structures from these canals in September.

Former DSCC mayor Sheikh Fazle Noor Taposh, earlier in July, expressed frustration at the obstacles posed by land grabbers and encroachers.

“Aggression in the name of government projects and the indifference of agencies are pushing us into more adversity,” he said, adding that unless this aggression could be curbed, Dhaka’s waterlogging problem would continue.

Since the fall of the Hasina regime on 5 August, the two city corporations have operated without mayors.

This week, Dhaka North’s new administrator, Md Mahmudul Hasan, described rescuing the canals as one of the toughest jobs in Bangladesh, noting, “We have started removing plastic and other waste, but freeing the canals from encroachments will take time.”

Regarding the eviction of illegal structures, he said, “A new eviction drive is challenging at the moment. The police force crisis and the socio-economic condition must be considered. We are reviewing illegal installations and identifying locations, hoping to start the campaign once the country stabilises.”

Dhaka South City Corporation Chief Executive Officer Md Mizanur Rahman said, “Mayor Taposh had drafted his own canal development plan. Under the new administration, we will proceed with demarcation as per a fresh plan.”

He added, “Removing waste and evicting illegal structures doesn’t keep canals clean for even 15 days. The canals are quickly reoccupied and polluted again. We will decide on measures to ensure sustainable progress, and hopefully, there will be lasting changes in the canals.”

Impact of urbanisation on Dhaka’s canals

The roots of Dhaka’s canal loss can be traced back to the city’s unplanned urbanisation.

According to a 2017 study by the Rajdhani Unnayan Kartripakkha (Rajuk), the city’s primary development authority, at least 72,000 illegal structures exist in flood-flow zones throughout the capital.

The number has only increased since then. Many of these structures have been built along, or directly over, Dhaka’s canals, choking the waterways and rendering them incapable of performing their original function.

The canals that once provided drainage and helped regulate Dhaka’s floodwaters have either been filled in or diverted into concrete culverts, leading to a sharp decline in the city’s water management capabilities.

The city, which should be able to absorb and redirect rainwater, instead experiences chronic waterlogging.

Moreover, the environmental impact of canal loss is felt through degraded ecosystems and increasing pollution levels in what remains of the waterways.

Expert opinions on canal restoration

Urban planners and environmental experts are not optimistic about the city corporations’ ability to tackle the canal issue without a fundamental shift in strategy.

Alamgir Kabir, general secretary of the Bangladesh Poribesh Andolon, criticised the restoration efforts, calling them superficial and aimed at embezzling project funds.

Kabir noted that Dhaka’s canal network, if properly restored, could alleviate the city’s traffic congestion by providing alternative transportation routes. “No other city globally possesses a canal network like Dhaka’s. But these canals are neglected.”

Professor Akter Mahmud from Jahangirnagar University’s Urban and Regional Planning Department underscored that illegal occupants must be evicted to restore the canals’ flow.

“Without this, developing Dhaka’s drainage system is not feasible, and the city’s environmental degradation will continue.”

Professor Mahmud, a former president of the Bangladesh Institute of Planners, advocated for the construction of walkways and cycle lanes along the canals to discourage further encroachment.

Syeda Rizwana Hasan stressed the need for the creation of a master plan to protect the canals. This plan, she said, should include clear boundaries, a database of canal records, and guidelines to prevent future encroachments.