Plight of Dhaka’s canals: Ravaged by encroachment, pollution, urbanisation

“Did you know that this road, where we are standing, was a canal two decades ago?” asked Abdus Sattar, a man in his late 70s, pointing to Panthapath Road.

“I used to fish and bathe here. Water from Hatirjheel flowed through this Panthapath Canal, passing through Dhanmondi Lake to the Buriganga River,” the elderly man said.

Expressing his frustration, Sattar said, “A box culvert was built over the canal to make this road. If the canal were still flowing, we could have boats on it. I have travelled to many countries in Europe and America and have never seen nature destroyed like this to build roads and buildings. It only happens in Bangladesh.”

He added, “The canal’s ownership changes every few years with various projects, but it never returns. If this continues, we will need binoculars to find a canal in Dhaka.”

At Mirpur, Sanowar Hossain, a resident of West Kafrul Ananda Bazar Road, said, “The Kalyanpur Canal used to flow through Kazirpara to Mirpur 2. Now it is a drain. Dhaka Wasa has made it smaller with concrete embankments. The water flow gets choked with garbage in winter.”

He showed pictures of flooded streets on his phone. “Even 2-3 hours of rain cause waist-deep water. Garbage from the canal reaches our houses. The city corporation has not cleaned it, and the constructed drain overflows, causing floods.”

Most Dhaka residents share Sattar and Sanowar’s concern about the city’s canals. They question if it is even possible to save them.

Over the years, ownership of Dhaka’s canals has shifted frequently among the district administration, city corporations, and Dhaka Wasa.

According to the district administration, there are 50 canals in Dhaka, while the two city corporations claim there are 46.

Currently, Dhaka North and Dhaka South city corporations manage 26 canals, while others remain under the Ministry of Housing and Public Works and the Bangladesh Water Development Board.

Dhaka loses 120km of canals in 83 years

A River and Delta Research Centre (RDRC) study reveals that Dhaka city has lost 120 km (307 hectares) of canals between 1940 and 2023.

Unplanned urbanisation and neglect led to the loss or significant reduction of 95 canals. Only 11 canals and 4 lakes have been newly excavated.

RDRC compared cadastral surveys from 1888-1940 with 2022 satellite images and identified 77 major canals and lakes in Dhaka.

These waterbodies covered 565 hectares, with about 55% now lost. Of the 307 hectares lost, 33.75% is occupied by structures, 18.92% by farmland, and 16.94% by streets. The rest has been filled or turned into wetlands. The survey, conducted in lean seasons, excluded foreshore and wetlands.

Begunbari, Ramchandrapur, Dholai, and Rampura canals have each lost over 3 km in length, while the Buriganga’s old channel lost 2.46 km and 18.63 hectares.

RDRC Chairman Mohammad Azaz noted that illegal occupation and pollution of rivers, canals, and other waterbodies have negatively impacted Dhaka’s environment.

“Dhaka faces a critical loss of waterbodies due to rapid urbanisation. Water and air pollution, waterlogging, groundwater depletion, and other crises have affected the city,” he said.

He questioned the responsible authorities’ efforts and urged the city corporations to act swiftly to restore the water flow in the canals. He stressed the need for government initiatives and holistic responses to preserve the remaining rivers, channels, lakes, and canals.

15 canals lost to urbanisation

Urbanisation has claimed at least 15 of Dhaka’s canals, now replaced by box culverts and roads. Authorities state these changes were made on government directives, but plans to restore the canals have not been implemented.

One such waterway was the Panthapath Canal, which connected Dhanmondi Lake to Hatirjheel Lake. Now buried under Panthapath Road, it once drained rainwater into Begunbari Canal.

Another waterbody, Paribagh Canal, which flowed from Shahbagh through Mogbazar, has now been replaced by Sonargaon Road.

The Arambagh and Gopibagh canals, once key waterways, have also been filled in. Similarly, the Rajabazar and Nandipara-Trimohini canals have been replaced by box culverts.

A particularly long canal, originating from Matsya Bhaban and traversing through several prominent areas, has also been converted into a road. The Kajlar Par Canal, once a vital water route for locals, is now the Kajla-Kutubkhali Road.

The Dholaikhal and Dayaganj canals have been filled in, contributing to waterlogging issues in the Dholaikhal-Dayaganj-Mirhajhirbag area. Even the Kathalbagan and Dhalpur canals have met a similar fate, with their spaces now occupied by land and infrastructure.

Many other canals have met similar fates, including the Rayerbazar, Segunbagicha, Gobindpur, Kathalbagan, and Narinda canals.

Dhaka Wasa cited government instructions for converting canals into roads.

“We constructed box culverts over canals in the 1990s through government decisions. Roads were needed at the time,” said AKM Shahid Uddin of Dhaka Wasa.

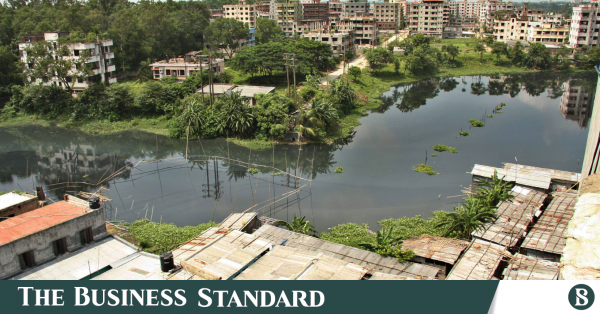

Current situation of existing canals

The Rupnagar Canal, once 2.43 km long and over 18 metres wide, is now a narrow drain. Encroachment by buildings and waste dumps has reduced its width to less than 2-3 metres in some areas.

Abdul Waset, a resident, expressed his dismay at the canal’s deterioration, noting that Dhaka North does not clean it regularly.

In Jatrabari, half of the Baishteki Canal has been turned into a road, leaving the remaining portion as a narrow, polluted drain.

The Kalyanpur Canal network, which includes six smaller canals, has been similarly encroached upon, despite official records indicating widths ranging from 8 to 40 metres.

The Hazaribagh Canal, once 3 km long, is now a waste heap. Small structures line its banks, and there is no water flow near the Hazaribagh sluice gate.

Asma Begum, a local resident, noted the severe waste problem and the lack of proper cleaning.

Similarly, the Jirani Canal, supposedly 5.5 km long and 20-30 metres wide, has been reduced to as narrow as 3-5 metres due to encroachment.

The Ramchandrapur Canal, once 3.1 km long, has been filled in at several points, while the Digun Canal in Mirpur has almost entirely disappeared.

Despite managing 26 canals for nearly four years, neither city corporation has restored regular water flow in any of them. Dhaka North spent Tk330 crore over four years, and Dhaka South invested Tk220 crore, but progress has been slow.

Dhaka South currently has a Tk900 crore project to revive four canals, including the construction of reinforced embankments. However, this project, scheduled to start in September 2021 and finish by December 2024, is yet to be implemented.

City corporations cite extensive encroachment and limited resources as major challenges to reviving Dhaka’s canals.

While they acknowledge that the restoration will take time, urban experts and environmentalists stress that proper implementation of existing policies is critical to addressing the crisis.